|

|

Introduction |

|

|

001

002

|

EPICURUS,

son of Neocles and Chaerestrate, was an Athenian from the district of Gargettus

district, of

the Philaidae clan, as Metrodorus reports in his book On Noble Birth.

Other sources, including Heraclides in his Epitome of Sotion, report that

he grew up in Samos, after the Athenians divided up the land for colonization,

and he came to Athens at age eighteen, when Xenocrates lectured at the Academy,

and Aristotle in Chalcis. But when Alexander of Macedon died, and the

Athenians at Samos were evicted by Perdiccas, Epicurus left Athens to join

his father in Colophon. He stayed there for some time and gathered disciples, then

returned to Athens during the archonship of Anaxicrates {307-306 BCE}. For

a while, he continued practicing philosophy with other philosophers, but

afterwards he eventually founded the philosophical sect which bears his name. EPICURUS,

son of Neocles and Chaerestrate, was an Athenian from the district of Gargettus

district, of

the Philaidae clan, as Metrodorus reports in his book On Noble Birth.

Other sources, including Heraclides in his Epitome of Sotion, report that

he grew up in Samos, after the Athenians divided up the land for colonization,

and he came to Athens at age eighteen, when Xenocrates lectured at the Academy,

and Aristotle in Chalcis. But when Alexander of Macedon died, and the

Athenians at Samos were evicted by Perdiccas, Epicurus left Athens to join

his father in Colophon. He stayed there for some time and gathered disciples, then

returned to Athens during the archonship of Anaxicrates {307-306 BCE}. For

a while, he continued practicing philosophy with other philosophers, but

afterwards he eventually founded the philosophical sect which bears his name.

He first encountered philosophy, as he himself says, at the age of fourteen. Apollodorus the Epicurean, in the first book of his Life of Epicurus,

reports that he turned to philosophy out of disgust with his schoolmasters,

because they could not explain to him the meaning of chaos in Hesiod.

|

|

|

003 |

Hermippus, however, asserts that he began his career as a schoolmaster, and was

then turned on to Philosophy by the works of Democritus. Hence, Timon

says:

The last of all the philosophers of physics,

And the most shameless too, did come from Samos,

A

schoolmaster like his father before him,

Himself the most uneducated of mortals.

|

|

|

|

At his exhortation, his three

brothers, Neocles, Chaeredemus, and Aristobulus, joined his sect, as Philodemus, the Epicurean, reports in

his tenth book On Philosophers. He had also a slave, whose

name was Mys, as Myronianus reports in his Historical Parallels.

Dubious and Slanderous

Accounts

|

|

|

004

005 |

Diotimus the Stoic was very hostile to him; he slandered

him egregiously, publishing fifty obscene letters, which he attributed to

Epicurus. Yet another author ascribed letters to Epicurus that were commonly attributed to

Chrysippus. Posidonius the Stoic, Nicolaus, and Sotion, in the twelfth book

of his 24-volume Refutations of Diocles, and Dionysius of Halicarnassus

also slandered him. They alleged that:

-

he used to go round

cottages with his mother fortune-telling and reading rites of purification.

-

he assisted at his father’s school for a pittance.

-

one of his brothers was a pimp and lived with

Leontium the courtesan.

-

he claimed the doctrines of Democritus, about atoms,

and of Aristippus, about pleasure, were his own.

-

he was not a genuine Athenian citizen (a charge

brought by Timocrates and by Herodotus in a book On the Training of

Epicurus as a Cadet).

-

he shamelessly flattered Mithras, the minister of

Lysimachus, bestowing upon him, in his letters, Apollo’s titles of Paean

{Healer} and Lord.

-

he flattered Idomeneus, Herordotus, and Timocrates,

for publishing his esoteric doctrines.

-

and that in his letters, he wrote...

-

to Leontium: “Oh

Lord Paean,

my dear

little Leontium, to what tumultuous applause we were inspired as we read

your letter.”

-

to

Themista, the wife of Leonteus:

“I am

quite ready, if you do not come to see me, to spin thrice on my own axis

and be propelled to any place that you, including Themista, agree upon.”

-

to the

beautiful Pythocles:

“I

shall sit down and await your lovely and godlike appearance.”

|

|

|

006 |

Also, Theodorus says in the fourth book Against Epicurus,

that:

-

in another letter to

Themista he had determined to make his way with her.

-

he also wrote to many other courtesans, especially to Leontium,

with whom Metrodorus also was in love.

-

in his book On the End-Goal, he writes, “I

do not know how to conceive the good, apart form the pleasures of taste, the

pleasures of sex, the pleasures of sound and the pleasures of contemplating

beauty.”

-

and that in his letter to Pythocles, he writes,

“Hoist all sail, my dear boy, and steer clear of all culture.”

|

|

|

007

008 |

Epictetus calls him a preacher of unmanliness and showers

abuse on him.

Even Timocrates, the brother of Metrodorus, who was his

disciple until he left the school, asserts in his book entitled Merriment,

that:

-

Epicurus vomited twice a

day from overindulgence

-

he himself had great

difficulty escaping this secret society with its night-long sessions.

-

Epicurus was rather ignorant

of philosophy, and his ignorance of real life was even greater.

-

his bodily health was pitiful, and for

that many years he

was unable to rise from his chair.

-

he spent a whole mina daily on his

table, and that he

himself says so in his letter to Leontium and in the one to the philosophers

of Mitylene.

-

among other courtesans who consorted with him and

Metrodorus were Mammarion, Hedia, Erotion, and Nikidion {“Mama,”

“Lusty,”

“Erotique,”

and “Victory.”}

-

in his 37 books On Nature,

he is overly repetitive and argumentative

-

he argued especially against

Nausiphanes, saying

“They

can go to Hades; when working

slavishly

with an idea, he too bragged like a Sophist.”

-

even in his letters,

Epicurus himself writes of Nausiphanes:

“So incensed,

he cursed me and called me schoolmaster.”

-

and that Epicurus disparaged many

philosophers:

-

Nausiphanes he

called a

pleumonon. {= “jellyfish,” imputing

insensibility}

-

Plato’s school he called the

“flatterers

of Dionysius.”

-

Plato himself: “Golden.”

-

Aristotle: a reckless spender, who,

after devouring his patrimony, took to soldiering and selling drugs.

-

Protragoras: a

“basket-carrier”

{phormophóron} and

“the scribe of Democritus” and a

“village schoolmaster.”

-

Heraclitus: a “muddler.”

-

Democritus: “Lerocritus” {the gossip-monger}

-

Antidorus: “Sannidorus” {a fawning

gift-bearer}

-

the Cynics:

“enemies

of Greece”

-

the

Dialecticians: “despoilers”

-

Pyrrho:

“ignorant” and a “bore.”

His Genuine Character

|

|

|

009

010 |

But all these people are devoid of sense. The

preponderance

of witnesses speak of the insuperable kindness of our philosopher to everyone,

whether it be to his own country who honored him with bronze statues, his

friends who are so numerous that they could not be counted in whole cities, or

all his acquaintances who were bound to him simply by the appeal of his

doctrines. None deserted him, except Metrodorus, the son of Stratoniceus, who went over to Carneades,

probably because he could not stand Epicurus’ unapproachable excellence. The

school itself, while every other school has declined, has continued in

perpetuity through an uninterrupted succession of head-philosophers. We may also

note his gratitude towards his parents, his generosity to his brothers, and his

kindness to his servants (as made plain by his will, and also from the fact that

they joined him in his philosophical pursuits, the most eminent of them being

the aforementioned Mys), and his universal philanthropy towards all men.

|

|

|

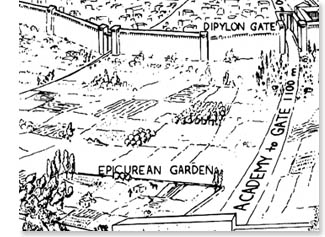

011 |

His

piety towards the gods and his love for his country are beyond words. His

deference to others was so keen that he did not bother to enter public life.

And although he lived while very difficult times oppressed Greece, he still

remained in his own country, only venturing two or three times out to Ionia to

visit his friends, who used to throng to him from all quarters to live with

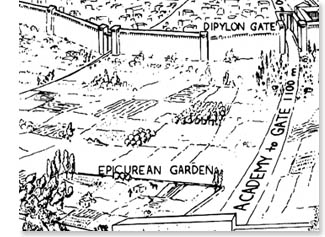

him in his garden, as we are told by Apollodorus (This

garden he bought for eighty minae). And Diocles, in his third Epitome,

says that they all lived in the most simple and economical manner; “They were

content,” he says, “with a small cup of light wine, or just drank only

water.” He also tells us that Epicurus forbade his companions from holding

property in common, unlike Pythagoras, who required it. Such a

practice, in his opinion, implied mistrust – and without trust there is no

friendship. And in his letters, he himself says that he is content with

water and plain bread, adding, “Send me some Cytherean cheese, so that if I wish

to have a feast, I may have the means.” His

piety towards the gods and his love for his country are beyond words. His

deference to others was so keen that he did not bother to enter public life.

And although he lived while very difficult times oppressed Greece, he still

remained in his own country, only venturing two or three times out to Ionia to

visit his friends, who used to throng to him from all quarters to live with

him in his garden, as we are told by Apollodorus (This

garden he bought for eighty minae). And Diocles, in his third Epitome,

says that they all lived in the most simple and economical manner; “They were

content,” he says, “with a small cup of light wine, or just drank only

water.” He also tells us that Epicurus forbade his companions from holding

property in common, unlike Pythagoras, who required it. Such a

practice, in his opinion, implied mistrust – and without trust there is no

friendship. And in his letters, he himself says that he is content with

water and plain bread, adding, “Send me some Cytherean cheese, so that if I wish

to have a feast, I may have the means.”

|

|

|

012 |

Such was the real character of the man who laid down the

doctrine that pleasure was the chief good. Athenaeus eulogizes him so:

Oh men, you labor for small things;

And out of greed, you engage in strife and wars.

Yet, nature’s wealth puts a narrow limit on desires,

While vain opinions are insatiable.

This is what the wise son of Neocles heard from the Muses,

Or at the sacred shrine of Delphi’s God.

And as we proceed, we shall understand this even better from

his doctrines and his maxims.

|

|

|

|

Among the earliest philosophers, Diocles reports that his

favorites were Anaxagoras (though he disagreed with him on some points) and Archelaus, the

teacher of Socrates. Diocles adds that he used to train his pupils to commit his

writings to memory.

|

|

|

013 |

Apollodorus, in his Chronology, asserts that he was a pupil of Nausiphanes

and Praxiphanes; but in his

letter to Euridicus, Epicurus himself denies this, saying that he was

self-taught. He and Hermarchus deny that Leucippus deserved to be called a

philosopher; though some authors, including Apollodorus the Epicurean, name him

as the teacher of Democritus. Demetrius the Magnesian, says that Epicurus was

a pupil of Xenocrates also.

|

|

|

014 |

He uses plain language in his works throughout, which is unusual, and

Aristophanes, the grammarian, reproaches him for it. He was so intent on

clarity that even in his treatise On Rhetoric,

he didn’t bother demanding anything else but clarity. And in his

correspondence he replaces the usual greeting, “I wish you joy,” by wishes for

welfare and right living, “May you do well,” and “Live well.”

Ariston says in his Life of Epicurus that he derived

his work entitled The Canon from the Tripod of Nausiphanes, adding

that Epicurus had been a pupil of his, as well of the Platonist Pamphilus in Samos. Further, that he began to study philosophy at twelve

years of age, and that he founded his own school at thirty-two.

|

|

|

015

016 |

Apollodorus’ Chronology further

reports that:

-

He was born i\n the third year of the 109th Olympiad {341

BCE}, in the archonship of Sosigenes, on the seventh day of the month Gamelion,

seven years after the death of Plato {347 BCE}.

-

At thirty-two, he first set up

his school at Mitylene, and after that at Lampsacus.

-

After spending five

years in those two cities, he came to Athens.

-

He ultimately died there at seventy-two –

in the second

year of the 127th Olympiad {271-270 BCE}, in the archonship of Pytharatus.

-

Hermarchus, the son of

Agemarchus and a citizen of Mitylene, succeeded him in his school.

He died, Hermarchus writes in his letters,

from a kidney stone {or prostate cancer}, after being ill for a fortnight. Hermippus relates that

he entered a bronze bath tempered with warm water, asked

for a cup of undiluted wine, and drank it. He then bade his friends

to remember his doctrines, and expired. Our epigram for him is expressed

like so:

“Farewell, and remember all my

teachings,”

This, Epicurus told his friends upon dying.

In a warm bath, he gulped down pure wine,

And sank into the chill of Hades.

{Palatine Anthology VII.106}

Such was his life, and such was his death.

|

|

|

|

His last will was written as follows:

Epicurus’ Will

|

|

|

017 |

I hereby bestow all my possessions to Amynomachus of Bate,

son of Philocrates, and to Timocrates of Potamos, son of Demetrius,

jointly and severally according to the gift-deed deposited

at the Metro-on, provided that they place my garden and

all that pertains to it in the care of Hermarchus of Mitylene, son of Agemarchus,

and his companions, and to whomsoever Hermarchus

leaves as his philosophical successors, so that they may live and study there,

dedicated to the practice of philosophy. And I call upon all those who

adhere to my teachings to help Amynomachus, Timocrates, and their heirs, to

preserve the garden community to the best of their ability, for all those to whom my immediate successors hand it down. As for the

house in Melite: Amynomachus and Timocrates

shall allow Hermarchus to live there the rest of his life, together

with all his companions in philosophy.

|

|

|

018 |

Out of the revenues transferred by me to Amynomachus and Timocrates, I will that they,

in consultation with Hermarchus, earmark provisions for:

-

funeral

offerings to honor the memory of my father, my mother,

my brothers, and myself;

-

keeping my birthday as it has been traditionally

celebrated, on the tenth day of the month Gamelion;

-

the customary gatherings of our entire school,

established in honor of Metrodorus and myself, on the twentieth day of every

month.

-

celebrating also, as I myself have customarily done:

-

the day consecrated to my brothers, in the month Poseideon;

-

the day consecrated to memory of Polyaenus, in the month Metageitnion.

|

|

|

019

020

|

Amynomachus and Timocrates shall be the guardians of Epicurus,

the son of Metrodorus, as well as the son of Polyaenus, as long as they

live and study philosophy under Hermarchus. Likewise,

they shall be the guardians of the daughter of Metrodorus, and when she

is of marriageable age, they shall give her to whomsoever Hermarchus shall

select from his companions in philosophy, provided she is well-behaved and obeys Hermarchus. Amynomachus and Timocrates shall

also, out of my estate proceeds, give them sufficient support each year, after due consultation with Hermarchus.

And they shall make Hermarchus co-trustee of the revenues, so that everything

may be done with the approval of that man who has grown old with me in the study

of philosophy, and who is now left as the head of the school. And when the girl comes

of

age, let Amynomachus and Timocrates pay her dowry, taking from my property a sum

deemed by Hermarchus to be reasonable.

They shall also provide for Nicanor, as I have done hitherto, so

that all those members of the school who have helped me in private life and have

shown me kindness in every way and have chosen to grow old with me in philosophy

should, so far as my means can go, never lack the necessaries of life.

|

|

|

021 |

All my books are to be given to Hermarchus.

And should anything happen to Hermarchus before the children

of Metrodorus grow up, Amynomachus and Timocrates shall provide, as much as

possible from the revenues bestowed by me, enough for their several needs, as

long as they are well-behaved. And let them take care of the rest of my

arrangements so that everything may be carried out, to the best of their

ability.

Of my slaves, I hereby emancipate Mys, Nicias, and Lycon:

I also give Phaedrium her freedom.

|

|

|

022

|

At the point of death, he also wrote

the following letter to Idomeneus:

“On this

blissful day, which is also the last of my life, I write this to you.

My continual sufferings from strangury and dysentery are so great that

nothing could augment them. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which

arises from the

remembrance of our past conversations, counterbalances all these

afflictions.

I am asking you to care for the children of Metrodorus, in a manner befitting

the devotion you have given to me and to philosophy since you were a youth.”

Such were the

terms of his will.

His Disciples and

Namesakes

|

|

|

023

024 |

He had a great number of

disciples, the most famous being Metrodorus of Lampsacus, son of Athenaeus (or

Timocrates) and Sande. From the time they first met, he never left him,

except once when he went home for six months, but then returned to him.

And he was a virtuous man in every respect, as Epicurus tells us in prefatory

dedications in his works, and in the third book of his Timocrates.

Being of such character, he gave his sister Bates in marriage to Idomeneus,

while he himself took Leontium, the Attic courtesan, for his concubine. He

bared all disturbances, and even death, without fear; Epicurus tells us so in

his first book on Metrodorus. He reportedly died seven years before

Epicurus himself, in the fifty-third year of his life. In the

aforementioned will, Epicurus stipulates many provisions about the guardianship

of his children –

an indication that he had been dead some time. His brother was also

a pupil of Epicurus, the aforementioned Timocrates

– a trifling, silly man. He had a great number of

disciples, the most famous being Metrodorus of Lampsacus, son of Athenaeus (or

Timocrates) and Sande. From the time they first met, he never left him,

except once when he went home for six months, but then returned to him.

And he was a virtuous man in every respect, as Epicurus tells us in prefatory

dedications in his works, and in the third book of his Timocrates.

Being of such character, he gave his sister Bates in marriage to Idomeneus,

while he himself took Leontium, the Attic courtesan, for his concubine. He

bared all disturbances, and even death, without fear; Epicurus tells us so in

his first book on Metrodorus. He reportedly died seven years before

Epicurus himself, in the fifty-third year of his life. In the

aforementioned will, Epicurus stipulates many provisions about the guardianship

of his children –

an indication that he had been dead some time. His brother was also

a pupil of Epicurus, the aforementioned Timocrates

– a trifling, silly man.

Metrodorus wrote the following works:

-

Against the Physicians, in three books

-

On Sensations

-

Against Timocrates

-

On Magnanimity

-

On Epicurus' Weak Health

-

Against the Dialecticians

-

Against the Sophists, in nine books

-

The Way to Wisdom

-

On Change

-

On Wealth

-

In Criticism of Democritus

-

On Noble Birth

|

|

|

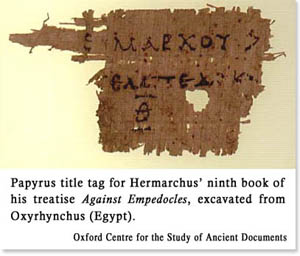

025 |

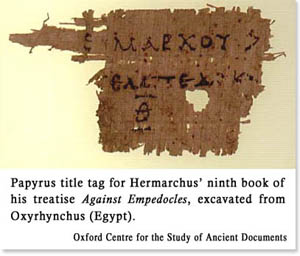

Similarly famous was Polyaenus of Lampsacus, son of

Athenodorus, a just and kindly man, as Philodemus and his disciples affirm.

Likewise

was Epicurus’ successor, Hermarchus of Mitylene, son of Agemortus (a poor man)

and originally a student of rhetoric. Likewise

was Epicurus’ successor, Hermarchus of Mitylene, son of Agemortus (a poor man)

and originally a student of rhetoric.

The following outstanding works by him are still extant:

Against Empedocles, in twenty-two books

On Mathematics

Against Plato

Against Aristotle

He died of paralysis, after fulfilling an excellent career.

|

|

|

026 |

There were also Leonteus of Lampsacus and his wife Themista,

to whom Epicurus wrote letters, and Colotes and Idomeneus, also of Lampsacus.

Hermarchus was succeeded in turn as head of the school by:

-

Polystratus

-

Dionysius

-

Basilides

-

Apollodorus, known as “the tyrant of the garden,” who

wrote over four hundred books.

-

The two Ptolemys of Alexandria: one dark-complected, the

other fair-skinned.

-

Zeno of Sidon, the pupil of Apollodorus and a prolific

author

-

Demetrius, who was called “the Laconian”

-

Diogenes of Tarsus, who compiled the select lectures

-

Orion

-

And there were still others whom the genuine Epicureans

call sophists.

There were three other men who bore the name of Epicurus: one, the son of Leonteus and Themista;

the second: a native of Magnesia; the third: a military chief.

His Works

|

|

|

027 |

Epicurus was a most prolific author,

exceeding all before him in number of books published: more than three

hundred volumes of them. In all these works, there is not one citation

of other sources; they are entirely filled with Epicurus’

own words. Chrysippus tried to match his vast literary output, but Carneades denounced him as a literary parasite: “Indeed, if Epicurus had

written something, Chrysippus would vie to write just as much. To

accomplish this, he wrote down whatever popped into his head and often

repeated himself. In his haste, he neglected to do any editing,

and he used many lengthy citations to the point of filling his entire

books with them, not unlike Zeno and Aristotle.”

|

|

|

028 |

Among the writings of

Epicurus, the following are his best:

-

On

Nature, in thirty-seven books

-

On

the Atoms and the Void

-

On Love

-

Summary

of Objections to the Physicists

-

Against

the Megarians

-

Problems

-

Principal Doctrines

-

On

Choices and Avoidances

-

On the

End-Goal

-

On the

Criterion, or The Canon

-

Chaeredemus

-

On the

Gods

-

On

Holiness

-

Hegesianax

-

On

Lifecourses, in four books

-

On Fair

Dealing

-

Neocles,

Dedicated to Themista

-

Symposium

-

Eurylochus, Dedicated to Metrodorus

-

On

Vision

-

On the

Angle of the Atom

-

On

the Sensation of Touch

-

On

Destiny

-

Theories of the Passions, against Timocrates

-

Prognostication

-

Exhortation to Study Philosophy

-

On

Images

-

On

Sensory Presentation

-

Aristobulus

-

On

Music

-

On

Justice and Other Virtues

-

On

Gifts and Gratitude

-

Polymedes

-

Timocrates, in three books

-

Metrodorus, in five books

-

Antidorus, in two books

-

Theories about Diseases [and Death], Dedicated to Mithres

-

Callistolas

-

On

Kingship

-

Anaximenes

-

Letters

|

|

|

029 |

I will attempt to present the views expressed in these

writings by reproducing three of his letters, in which he himself has given a

summary of his entire philosophy. I will also reproduce his Principal

Doctrines and some other sayings worth citing, so that you may be

thoroughly acquainted with the man, and know how to judge him. The first

letter, written to Herodotus, deals with physics; the second, to Pythocles,

deals with heavenly phenomena; the third, to Menoeceus, contains teachings

concerning human life.

His Three Divisions of

Philosophy: Canonics, Physics, and Ethics

|

|

|

030

031 |

But first: some few preliminary remarks about his division of

his philosophy. It is divided into three subjects: Canonics, Physics, and

Ethics. Canonics forms the

introduction to the system and is found in a single work entitled

The Canon. Physics consists of a comprehensive theory of nature; it is

found in the thirty-seven books On Nature and is also summarized among his Letters. Ethics, finally, deals with choice and avoidance,

which may be found

in the books On Lifecourses, among his Letters, and in the book

On the End-Goal. Canonics and Physics are usually treated

jointly. The former defines the criterion of truth and discusses first

principles (the elementary part of philosophy), while the latter deals with the

creation and destruction of things in nature. Ethics counsels upon things

chosen versus those avoided, the art of living, and the end-goal. Dialectics they

dismiss as superfluous –

they say that ordinary terms for things is sufficient

for physicists to advance their understanding of nature.

Some Elaboration on Canonics

|

|

|

|

Now in The Canon Epicurus states that

the criteria of truth are:

-

sensations {tas aistheses},

-

preconceptions {prolepses},

-

and feelings {ta pathon}.

Epicureans in general also include: mental images focused by thought.

His

own statements are also to be found in the Letter to Herodotus and the

Principle Doctrines.

“Sensation,” he says, “is non-rational and unbiased by memory, for it is neither produced spontaneously {inside the mind} nor can

it add or subtract

information from its external cause.

|

|

|

032 |

“Nothing exists which can refute sensations. Similar sensations cannot refute

each other {e.g., things seen}, because they are equally valid. Dissimilar

sensations cannot either {e.g., things seen versus things heard}, since they do

not discriminate the same things. Thus, one sensation cannot refute another,

since they all command our attention. Nor can reason refute sensations, since

all reason depends on them. The reality of independent sensations

confirms the truth of sensory information (seeing and hearing are real, just as

experiencing pain is).

“It

follows that we can draw inferences about things hidden from our senses only

from things apparent to our senses. Such knowledge results from applying

sensory information to methods of confrontation, analogy, similarity, and

combination, with some contribution from reasoning also.

“The visions produced by

insanity and dreams also stem from real objects, for they do act upon us; and

that which has no reality can produce no action.”

|

|

|

033 |

Preconception, the

Epicureans say, is a kind of perception, correct opinion, conception, or general

recollection of a frequently experienced external object. For example:

‘Such-and-such kind of thing is a man’ – as soon as the word ‘man’ is uttered,

the figure of a man immediately comes to mind as a preconception, already formed

by prior sensations.

|

|

|

|

Thus, the first notion a word awakens in us is a correct one;

in fact, we could not inquire about anything if we had no previous notion of it.

For example: ‘Is that a horse or an ox standing over there?’ One must have

already preconceived the forms of a horse and an ox in order to ask this.

We could not even give names to things if we had no preliminary notion of what

the things were. It follows that preconceptions clearly exist.

|

|

|

034 |

Opinions also depend on preconceptions. They serve as our point of reference when we ask, for example, ‘How do we

know if this is a man?’ The Epicureans also use the word assumption

for opinion. An opinion may be true or false.

True opinions are confirmed and uncontradicted {by the testimony of sensations};

false opinions are unconfirmed and contradicted {by the testimony of

sensations}. Hence they speak of awaiting {testimony} when

one awaits a closer view of an object before proclaiming it to be, for example,

a tower.

|

|

|

|

Feelings they say are two: pleasure and pain, which

affect every living being. Pleasure is congenial to our nature, while pain

is hostile to it. Thus they serve as criteria for all choice of avoidance.

They also say that there are two kinds of philosophical

inquiry: one concerns facts, the other mere words.

This, then, covers the basic points regarding philosophical

division and each criterion. Now we shall turn to his letter {which

discusses the basic principles of physics}:

Letter to Herodotus

A Summary of Physical Nature

Reasons for the Letter

Epicurus to Herodotus, Greetings,

|

|

|

035 |

For those, Herodotus, who can neither master all my physical

doctrines nor digest my lengthier books On Nature, I have written a

summary of the whole subject in enough detail to enable them to easily remember

the most basic points, and thereby grasp these important and irrefutable

principles entirely on their own, to whatever degree they take up the study of

physics. Even those who have thoroughly learned the entire system must be

able to summarize it, for an overall understanding is

more often needed than a specific knowledge of details.

|

|

|

036 |

We must therefore continually refresh our memory with these

principles, in order to retain the general outline. Moreover, once the

basic points have been mastered, specific knowledge of details can be learned

more easily. But the most important benefit of specific knowledge,

even for the fully-initiated, is that it reinforces a general understanding of

the fundamental principles. Indeed, it is impossible to reap the rewards

of further studying the universe, unless one can comprehend in simple terms all

that could be expressed in great detail.

|

|

|

037 |

Since this pattern of study is useful to everyone

concerned, I, who devote myself continuously to the subject and who am most at

peace by living this sort of life, have prepared for you a summary and outline

of my entire teachings.

Rules of Procedure |

|

|

038

|

First, Herodotus, we must use clearly defined terms, so that

when we refer to them, we can make judgments upon particular inquiries,

problems, or opinions, rather than to remain undecided after endless arguments

devoid of meaning.

Thus, we must accept, without further proof, the first mental

image each word conjures up, if we are to have any standard to refer a

particular inquiry, problem, or opinion. Next, we must conduct all our

investigations based on the testimony of our senses, feelings, and all other

valid criteria. In this way, we shall have some sign by which to make

inferences about things awaiting confirmation <by the testimony of our senses>

and also about things <that will always remain> hidden from our senses.

Basic Aspects of Existence |

|

|

039

|

Having made this distinction,

let us now consider what is not directly evident to our senses:

Nothing comes into existence

from non-existence. For if that were possible, anything could be

created out of anything, without requiring seeds. And if things which disappear

became non-existent, everything in the universe would have surely vanished by now.

But the universe has always been as it is

now, and always will be, since there is nothing it can change into. Nor is

there anything outside the universe which could infiltrate it and produce change.

|

|

|

040 |

The universe is made up of

bodies and void. That bodies exist is obvious to anyone’s

senses. We may also make inferences about things

hidden from our senses, as I have noted above, only from signs that our senses

can detect, and this is how we infer the void. For if the

void, which we also call place, room,

and intangible substance, did not exist, bodies would have no place

to be or anywhere to move through

– but they are clearly seen to be moving. Beyond these constituents

[body and void] nothing else is conceivable by any means. Both are

regarded as whole substances

– not

attributes of them.

|

{1} |

|

041 |

Compounds are collections of

many elements; the primary bodies are the elements themselves.

The latter must be uncuttable {atomic}, and permanent – otherwise all

things would crumble into non-existence. Some elements must be

strong enough to survive the dissolution of compounds; these are fully solid by nature, incapable of

dissolution to any degree. So these primary bodies must be

uncuttable bodies.

|

{2} |

|

042 |

The universe is infinite.

For that which is finite has an outmost edge, and an outmost edge can only be

found in comparison to something beyond it <but the universe cannot be so

compared>, hence, since it has no outmost edge, it has no limit; and since it

has no limit, it must be unlimited and infinite. Indeed, the universe is

infinite in two aspects: by the number of bodies it contains and by the extent

of the void. For if the void were infinite but the bodies finite, the bodies

would go careening through the infinite void and never stay put, owing to the

lack of other bodies to hinder and coral them by colliding with them. And if

the void were finite, there would be no room for infinite bodies.

|

|

|

043 |

The atoms have a unimaginable variety of shapes. Since

all compounds are formed by (and dissolve into) solid atomic bodies, the many varieties of compounds that exist

can only arise from an

unimaginable number of atomic shapes. But while the number of atoms of

each shape is utterly infinite, the number of shapes is not utterly

infinite, just unimaginably many, <otherwise atoms would have an infinite range

of sizes, which would defy observation>.

|

{3} |

|

044 |

The atoms are in constant motion throughout eternity.

{some text missing} Some get separated by great distances from each

other. Others oscillate in one place whenever they happen to get entangled

into a compound, or surrounded by a compound. It is the nature

of both bodies and void which allows this oscillatory motion. For the

bodies, being solid, rebound on collision to whatever distance their

entanglement allows them, while the void offers no resistance in the intervening

space. This may continue until at last the repeated shocks bring on the

dissolution of the compound. There is no beginning to all these motions;

the atoms and void

are eternal.

|

{4}

{5} |

|

045a |

These above points, if remembered, should suffice as an

outline for developing an understanding of the basic aspects of existence.

|

|

|

|

{Misplaced text 45b moved to 73 below}

The Mechanics of Sight |

|

|

046a

047b |

Images abound

which resemble the outlines of shapes. These husk-like

emanations [of atoms] are the thinnest things perceivable. Their existence

is possible

because in the space around us, appropriate conditions exist to accommodate their

hollowness and thinness, thus preserving the same orientation and shape as

the surfaces they are thrown off from. These outlines we call ‘images.’

{Misplaced text 46b & 47a moved to 61 below}

That the images are exquisitely thin is uncontested by anything evident, for they move with insuperable speed and arrive at our eyes

together. We thus know that their passage is met with little or no resistance,

whereas many, indeed all, compounds suffer immediate collisions.

|

|

|

048 |

The creation of images

happens as fast as thought. They are cast off continuously, in outline

form, from the surfaces of compounds

– obviously

without wasting away, thanks to reciprocal replenishment. The orientation

and arrangement of atoms in an image usually correspond to the emitting surface

without distortion. But sometimes images get combined in midair.

This fusion happens quickly since no interactions are required within the volume

of space contained by their outlines. There are also other ways in which

images are produced. None of these facts are contested by our sensations,

when we consider how sensation brings us coherent visions of objects around us.

|

|

|

049

050 |

Sight and perception are due to images received directly

from the surfaces of objects. We would not perceive their shape or

color very effectively if their emanations were actively mediated by the intervening air

{as Democritus believed}, or by means of light-rays or some sort of flowing

current directed to us by them. Rather, we are directly impacted by husks

from the objects, which share the color and shape of their source, but are thin

enough to penetrate our senses. Since these are cast off in rapid

succession (in sympathy with the vibrations of atoms in the depths of the

object), they present an uninterrupted image and preserve their relationship to

the source. Visual Impressions

versus Opinions |

|

|

051 |

The mental picture formed by intense visual scrutiny

or concentrated thought,

is true. Because this sort of picture is created by the

continuous impact of imagery,

or by the actual residue it leaves

behind, the shapes or properties of an external object are thereby correctly

revealed. Falsehood and error reside in opinion.

When <an image awaiting> confirmation (or at least non-contradiction) from

further sensory evidence fails to be so confirmed <or is contradicted>, this is

due to the embellishment of the image by opinion. {text uncertain here,

perhaps also some missing} ... For the mental pictures that

come to us either in sleep, or by concentration, or by the other instruments of

judgment, would not have such similarity to those things we deem to truly exist

if there were not some kind of flow of material actually coming to us from the

objects. And error would

not exist if we did not also permit within ourselves some other activity similar

<to the purposeful apprehension of mental images>, yet different. It is through

this other activity {i.e., forming opinions} that, when unattested or contested,

produces falsehood, and if attested

or uncontested, truth.

|

{6} |

|

052 |

This principle too, then, is important to maintain.

Otherwise, the criteria based on self-evident impressions would be destroyed and

falsehood would be taken as well-established as truth, throwing everything

into confusion.

Hearing |

|

|

053 |

Hearing results from a sort of current. It

may come from a person who speaks, or an

object that rings, bangs, or produces any sort of auditory sensation. This current is dispersed into particles,

all alike, preserving their common relationship with a well-defined continuity

extending all the way back to their origin. When hearing occurs, the

source is usually recognized; failing that, it at least reveals that something

is out there. Without this common relationship stemming from the source,

there would not be such awareness. We should not believe that the air

itself is shaped by the spoken word or sound, for the nature of air is hardly

shapeable. Rather, the effort of speaking squeezes out certain particles

in a breath-like stream that produces auditory sensations in the person we are

speaking to. Smell |

|

|

|

The sense of smell, like hearing, also depends on a

current. Here again, certain

particles flow away from an object that are suitably-sized to pass into this senses.

Some kinds of smells are disharmonious and unwelcome, others

harmonious and welcome.

Atomic

Properties |

|

|

054 |

Atoms only have shape, weight, size,

and attributes of shape {e.g., smoothness or roughness}. While

qualities of compounds change, the atoms do not change at all, since something

solid and indestructible must persist in order to make change

possible. Change results from rearrangements of certain particles –

or from their addition and

removal (but never to or from non-existence). Hence these particles

are interchangeable, but unchangeable –

their own particular weights and shapes persist.

|

|

|

055 |

Even when objects we ordinarily see are chipped away at,

they still retain shape, weight, {and size} –

while other qualities do

not remain but vanish entirely. The properties which endure suffice for the

variety of compounds in nature; it is necessary that

at least these properties remain and not be annihilated.

|

|

|

056 |

Atoms differ in size, but are not of every size.

We must not think otherwise, lest the visible world prove us wrong. The

evidence of our differing feelings and sensations is best explained if atoms differ in

size, but they need not be of every size in order to account for qualitative

differences that we perceive. If atoms were of every size, some would

have to be large enough to see. Clearly this isn’t so, and it’s impossible

to suppose how an atom might become visible.

Atomic

Parts |

|

|

057 |

No finite body has infinite parts, and all parts must have

a lower limit to size. We must reject the idea that something finite can be cut smaller and smaller

forever

– for then all

physical objects would be

brittle and we could, in concept, exhaust any compound

{by infinite cuts} and thereby completely annihilate it.

But we also cannot suppose there are infinite parts in a finite thing,

for this raises an immediate problem: how can something containing infinite

parts itself be finite? Each part must extend to some

size, and however small they may be, an infinity of them would have to extend to

infinite size. But a finite body has a visible extremity

– even if

we can't isolate it. We may suppose the outermost part has a

similarly-sized neighboring

part, and likewise in sequence, but not without end.

|

|

|

058 |

Consider the smallest width we can possibly

see: it’s both like and unlike a span. While it

seems to have properties in common with an extended object, it has no

distinguishable parts. If we attempt to distinguish parts – one on this

side, the other on that – neither of them can be visibly smaller than the whole

minimum. All we can do is inspect the minima in sequence and we neither

find them all in the same place, nor can we find the places where they touch

each other. Yet, in their own peculiar way, they build

size – the larger the size, the more minima there are; the smaller the size, the fewer.

|

|

|

059 |

The same description applies to the smallest

atomic size. Obviously, the smallest part of an atom is much smaller

than the smallest width we can see. But here again we can follow the same

analogy as we did with our claim that the atom has size: we draw the analogy

from the scale of seeable things. Hence, the atomic minima must be

regarded as fixed units, which may serve, at least in our imagination, as a

means of reckoning atomic size. But this is as far as the

analogy can go. We should not take it so far as to think that atoms can be

constructed or changed by arranging or rearranging atomic minima, because it is

impossible for atomic minima to be moved individually.

Atomic

Motion |

|

|

060 |

There is no top and

bottom in infinite space, but up and down are still

meaningful. For wherever we stand it is possible to project a line

above our heads, or below our feet, stretching to infinity. It is possible

to do both without confusing each direction with the other. Therefore it

is also possible to regard one type of motion as upward to infinity, and

another type as downwards to infinity. Even if that which moves

from where we are to the places above our heads arrives countless times at the

feet of those above, or in the other case, at the heads of those below, the two

motions are still opposite.

|

|

|

061 |

Atoms move equally fast

through the void when nothing collides with them. Large and heavy ones

move no faster than small and light ones, nor vice a versa, as long as nothing

obstructs them. Their movements are neither made quicker when deflected

upwards or sideways, nor when they fall downwards due to their respective

weights. The atom will traverse any kind of trajectory with the speed of

thought as long as the motion caused in either of these ways maintains itself –

that is, until the atom is either re-deflected by another collision, or its own

weight counteracts the force of a previous collision.

|

|

|

046b |

Motion through the void may traverse any ordinary distance in

an extraordinarily short time, because the lack of obstruction from colliding bodies.

Only through collision and non-collision can atomic motion resemble

“slow” and “fast.”

|

|

|

047a |

On the other hand, a moving body cannot arrive at several

places at once in the shortest conceivable period of time. That is

unthinkable. But when in a perceivable period of time a body

arrives along with others from some point or other in the infinite, the distance

covered will be extraordinary. If it were otherwise, collisions would have

been involved – though we still allow some limit to speed of motion as a result

of non-collision. This too is a useful principle to grasp.

|

|

|

062 |

Atoms also move equally fast in compounds, despite

anything said to the contrary. Compounds, and the atoms within them,

do move in a single direction in the shortest perceivable period of time.

But in the shortest conceivable period of time, the atoms are going every

direction, owing to their frequent collisions. Only the continuity of their

collective

motion is slow enough to be seen.

The opinion (added to what the senses cannot perceive) that

“there will be continuity of motion in conceivable periods of time” is

not true in the case of atoms. Only what is grasped by the

careful use of the senses or by the mental apprehension of concepts is wholly true.

The Soul |

|

|

063 |

The soul is a fine-structured

material distributed throughout the body. Our sensations and feelings

provide the strongest confirmation for this. It resembles a wind in some

respects and heat in others. But its fine structure makes it greatly

different from both – and this is what unites its feelings with the entire body.

All this is demonstrated by the soul’s

powers: its feelings, its rapid action, its thought processes, and all of its

faculties which we are deprived of upon death.

|

|

|

064 |

The soul is primarily

responsible for sensation. Yet,

it would not have acquired sensation if it were not contained in some way by

the rest of the body. The rest of the body, having furnished the

proper setting for experiencing sensation, is also given some capacity

for sensation from the soul – though not all the capacity of the soul.

That is why the rest of the body does not have sensation when the soul has been

separated from it. For the body never had such capacity in and by itself;

it made sensation possible for something else [the soul], which came into

existence along with it. The soul, thanks to the mechanisms of the body,

at once produces its own power to experience sensation while returning a share

of this power to the body, as I have said, because of their close contact and

united feelings.

|

|

|

065

066 |

Sensation is never lost when the soul remains, even if

other parts of the body are lost. Indeed, even if part of the

soul is lost along with the part of the body that enclosed it, then as

long as part of the soul remains, it will still experience sensation.

But sensation is lost when the body remains and the soul

has been lost – no matter how small the atoms comprising the soul may be.

When the whole body is destroyed, it no longer possesses

sensation, because the soul is dissolved and no longer has the same powers

and motions. For whenever the body holding the soul is no longer able to

confine and contain it, we cannot think of the soul as still experiencing

sensation, since it would no longer have the use of the appropriate mechanisms.

|

{7} |

|

067 |

Those who say that the soul is incorporeal are talking

nonsense. The usage of the word ‘incorporeal’ can only be applied to

what is incorporeal in essence: the void. But the void can neither act

nor be acted upon; it merely allows bodies to move through itself.

For if that were so, it would be unable to act or be acted upon in any way –

yet, we clearly see the soul is capable of both.

|

|

|

068 |

If, as was said at the beginning, you explore your feelings

and sensations while considering these points about the soul, you will find

enough of a basis in this outline to enable you to discover the details with

certainty.

Properties and Accidents |

|

|

069 |

Shapes, colors, sizes,

weights, etc., are properties pertaining to bodies. This is true for

bodies in general as well for perceivable ones, where properties are recognized

by direct sensation. Properties are not substances themselves – it is

inconceivable to think of them separate from the things they are properties of.

Nor are they non-existent, nor are they incorporeal things attached to the body,

nor are they parts of a body.

|

|

|

|

A body as a whole gets its

enduring characteristics from the combination of all its properties.

This does not mean that these properties come together and form the body in the

way that a larger body is formed by smaller parts (e.g., by primary bodies or

compounds smaller than the whole). We merely mean, as I have said, that

the whole body gets its enduring characteristics from the presence of the

properties within. These properties have their own way of being perceived

and distinguished (together with the body – never separate from it); it is

because of this all-inclusive notion of the body as a whole that it is so

recognized.

|

|

|

070 |

Now it often also happens that temporary qualities accompany body –

accidents. They too do not exist by themselves nor are they incorporeal.

Accidents are neither like the whole, which we grasp collectively as a body,

nor are they like the enduring characteristics essential to a body. Any

accident can be recognized by the appropriate senses, along with the compound to

which it belongs; but we see a particular accident only when it is present with

the body, since accidents are temporary.

|

|

|

071 |

We must not deny the self-evident reality of accidents, just because they do not

have the nature of the whole (i.e., the

body, of which it becomes an attribute) nor the nature of permanent attributes. Nor

should we think of them as entities having independent existence. We should think of

accidents of bodies as just what they seem to be and not as permanent attributes

nor as existing independently. They are seen in just the way that our

senses discern them.

|

|

|

072 |

Time is something else that must also be carefully considered.

We cannot investigate time in the same way we can for things that can

be seen in objects and visually apprehended by the mind. Instead, we must

reason by analogy from the experience of what we call “a long time” versus “a

short time.”

|

|

|

073a |

We do not need better descriptions of time; we may use those

already at hand. Nor do we need to assert that this unique entity is based

on something else of the same nature, as some indeed do. It is only

important to consider the things we associate with time and the ways in which we

measure it. This requires no elaborate demonstration – only a review of

the facts. We associate time with days and nights (and fractions

thereof), and likewise with the presence and absence of feelings, and with

motions and rests. Thus we recognize that the very thing we call time is, in a special

sense, an accident of accidents.

World-Systems |

{8} |

|

045b |

The number of world-systems

is infinite. These include worlds similar to our own

{which means the Earth plus the sky and all its celestial bodies} and dissimilar

ones. For the atoms, being infinitely many, as already proved, travel any

distance, and those which are able to form a world are not exhausted by the

formation of one

world or by any finite number of them – both ones like ours or other

kinds. So nothing prevents there being an infinite number of worlds.

|

|

|

073b |

{World-systems, like all compounds, are perpetually

created and destroyed}. The world-systems, and every observable compound, come into being from the infinite. All such

things, large or small, have been separated off from it as a result of

individual entanglements. And all will disintegrate back into it – some

faster, some slower, and by differing causes.

|

{9} |

|

074 |

{text missing} Though the creation of worlds is inevitable,

we must not suppose that each necessarily has a single shape <or every possible

shape...>

|

{10} |

|

|

{text missing} <... Moreover, with regard to living things,>

it cannot be proven that the seeds from which animals, plants, and other things

originate are not possible on any particular

world-system.

Natural History |

{11} |

|

075 |

In their environment, primitive men were taught or

inspired by instinct to do many kinds of things, but reason later built upon

what had been begun by instinct. New discoveries were made – faster

among some people, slower among others. In some ages and eras <progress

occurred by great leaps>, in others by small steps.

|

|

|

076 |

Words, for instance,

were not initially coined by design. Men naturally experienced

feelings and impressions which varied in the particulars from tribe to tribe, so

that each of the individual feelings and impressions caused them to vocalize

something in a particular way, in accordance also with differing racial and

environmental factors. Later, particular coinages were made by consensus within

the individual races, so as to make the distinctions less ambiguous and more

concise. Men who shared knowledge also introduced certain abstractions,

and brought words for them into usage – sometimes making utterances

spontaneously, and other times choosing words rationally. This is mainly

how they achieved self-expression.

Celestial Phenomena |

|

|

077 |

Celestial phenomena do not occur because there is some divinity in

charge of them. No deity could arrange and maintain motions,

periods, eclipses, risings, settings, and the like, while at

the same time enjoy perfect happiness and immortality. For trouble,

anxiety, anger, and obligation are not associated with blessedness,

but rather with weakness, fear, and dependence on others. Masses of

fire [are not gods]; they have not acquired a state of divine blessedness

nor have they undertaken these motions of their own free will. Whenever we

speak of blessedness, we must respect [the true meaning

of] its majesty, or else we shall create great turmoil in our souls. So it stands to

reason that when celestial bodies were formed (at the time our world-system was created) the regularity of their motions was

fixed.

|

|

|

078 |

We must accept the following beliefs:

-

The purpose of physics is to correctly identify the causes of

phenomena that concern us.

-

Our happiness depends on this, and on knowing what

celestial bodes really are, and on related facts.

-

Anything that suggests conflict or disturbance in divine

nature simply cannot occur – there are no two ways about it.

-

It is possible for the human mind to reason out that all

this is true without

qualification.

|

|

|

079 |

Detailed celestial data do not

contribute to the happiness which comes with

general knowledge. Those who have studied settings and

risings, periods and eclipses, and the like, but are ignorant of their

underlying nature and their causes are subject to the same fears

despite what they know – or perhaps even greater fears, because the amazement that

follows from studying these phenomena does not reveal their fundamental causes.

|

|

|

080 |

If we find several possible causes for some celestial

phenomena, we have not failed to learn enough to secure peace of mind and

happiness. In order to investigate the causes of celestial phenomena

(or anything else which cannot be

scrutinized up-close) we begin by finding how many ways similar phenomena are

produced within the range of our senses. We must pay no attention to those

who fail to recognize any difference between what results from a single cause or

from several causes; they forget that these phenomena are only perceived at a

distance, and they do not know what circumstances make it possible or impossible

to achieve peace of mind. If we recognize that phenomena may occur in

several ways, we shall be

no less disturbed than if we knew for sure that a particular phenomenon happens

in some particular way.

|

|

|

081 |

Additionally, the worst turmoil in human souls arise because:

-

They think that celestial bodies are blessed and immortal

[i.e., godlike] yet desire, scheme, and act in ways that are incompatible

with divine nature.

-

They either foresee their deaths as eternal suffering, as

depicted in myths, or they fear the very lack of consciousness that

accompanies death as if it could be of concern to them.

-

They suffer all this not because there is a reasonable

basis, but because of their wild imagination; and by not setting a limit to

suffering, their level of turmoil matches or exceeds what they would suffer

even if there was a reasonable basis.

|

|

|

082 |

Peace of mind comes from having been freed from all this,

and by always remembering the essential principles of our whole system of

belief. Thus, we should pay attention to those feelings and sensations

which are present within us (both those we have in common with humankind at

large, and the particular ones we have in each of ourselves) according to each

of the criteria of truth. Only then shall we pin down the sources of

disturbance and fear. And when we have learned the causes of celestial

phenomena and related events, we shall be free from whatever is terrifying to

the rest of humankind.

Conclusion |

|

|

083 |

Here then, Herodotus, you have the most important points of

physics set down in an outline form that is suitable for memorization. I

believe that anyone who masters this much will be made stronger than his fellow

men, even without going into a more detailed study. And one will also be

better disposed to understanding many detailed points of our system as a whole

[should he elect to do so]; these general principles will be of constant help if

he keeps them in mind. For no matter how far along one is in mastering the

details, those who solve their solve their problems with reference to this

outline will make the greatest advances in the knowledge of the whole. And

even those who have made less progress can, without oral instruction, quickly

review the matters of most importance for peace of mind.

This concludes his letter on Physics. Now lets

look at his letter on heavenly phenomena

|

|

|

|

Letter to Pythocles

A Summary of Phenomena of the Sky

Occasion for the Letter |

|

|

084 |

Epicurus to Pythocles, Greetings,

|

|

|

085 |

Cleon brought me your letter, in which you show kindness

towards me worthy of my affection for you, and you tried, not unconvincingly,

to recall the lines of reasoning that lead to a happy life. You ask me to

send you a brief account of phenomena of the sky, concise enough to be easily

remembered, because what is written in my other books, as you say, is difficult

to remember even with continual study. I am pleased to yield to your

desire, and I have good hope that it shall also be useful to many others,

especially to those who have only recently become acquainted with the true

teachings about the natural world and to those who are too busy in their daily

lives to devote much time to more advanced study. So carefully grasp these

principles, memorize them thoroughly, and meditate on them along with what I sent in the Small Summary

addressed to Herodotus.

The Reason for Studying this

Subject |

|

|

|

We begin by recognizing that knowledge of the phenomena of

the sky, whether discussed along with other doctrines or separately, has no

other purpose than for peace of mind and fearlessness, just as it is in all our

other pursuits.

The Dogmatic

Method does not Apply |

|

|

086 |

It is unwise to desire what is impossible:

to proclaim a uniform theory about everything. So here we cannot

adopt the method that we have followed in our discussions of ethics, or our

solutions to problems of physics (e.g., that the universe consists of bodies and

void, that atoms are elementary to all things, and so on). For those we

gave a single precise explanation for every fact, consistence with the evidence

of the sense.

|

|

|

087 |

The phenomena of the sky, however, present a different

situation. Each of these phenomena allow several differing explanations

for its creation and its nature, all of which may agree with visible evidence.

Rather than committing to explanations based on unwarranted assumptions and

dogma, we may only theorize as far as the phenomena allow. For our life

has no need of unreasonable and groundless opinions; our one need is untroubled

existence. So if one is satisfied, as he should be, with that which is

shown to be less than certain, it is no cause for concern that things can be

explained in more than one way, consistent with the evidence. But if one

accepts one explanation and rejects another that is equally consistent with the

evidence, he is obviously rejecting science altogether and taking refuge in

myth.

|

|

|

088 |

Things we know and understand to happen on earth are

sometimes analogous with phenomena of the sky. But since the latter may be

due to a variety of causes, our observations of each may be reckoned with a

variety of earthly analogies.

World-Systems |

|

|

|

A world-system is a finite part of the universe,

encompassing celestial bodies, the earth, and all their phenomena.

It is separated from the infinite <by a finite boundary which, when it perishes,

all within it will be thrown into chaos. This boundary is:

All are possibilities, since

no contradictory evidence can be seen; we cannot even see the boundary of our

own world.

|

|

|

089

090 |

World-systems, which are knowably infinite, come into

being either in the spaces between or within other world-systems.

They form in places that are mostly empty (but not absolutely empty, as some

think) when the appropriate seeds (from one or several worlds or anywhere in

between) pile up. This occasions further accumulation (and possibly

relocation) until the new

world is complete and durable, and it will last as long as the foundation

underlying it continues receiving new material. It’s not good enough to

say, as one of the so-called physicists {Democritus?} has said, that there

merely needs to be a reunion of elements, or some colossal whirl in the void

compelled by necessity, and that the world keeps growing in size until it bumps

into another world – for this goes against the evidence.

Celestial Bodies |

|

|

|

The sun, moon, and other celestial bodies were created

along with the rest of the world-system. They were not formed

beforehand and later drawn by into our world. Rather, they immediately

began to take shape and grow, as did the earth and sea, by means of a whirling

accumulation of fine parts of some type (either airy or fiery or both).

This is what the evidence suggests.

|

|

|

091 |

The sun, moon, and other celestial bodies are about large

as they appear to be. They may actually be a little larger, a little

smaller, or exactly the same size as at what we see, just as signal-fires on

earth, when seen from distance, appear to vary. Any objection to this

point will be easily overthrown, if one pays attention to the clear evidence, as I

demonstrate in my books On Nature.

|

{12}

{13} |

|

092 |

The risings and settings of the sun, moon, and other celestial bodies may be

due to:

-

The

kindling and quenching of their fires (supposing that the places of their

rising and setting are configured to make them happen).

-

Their uncovering and

re-covering by the rim of the earth.

-

Their motions being connected

to the revolution of the whole sky.

-

Their motions (supposing the

whole sky does not revolve) being predetermined since the creation of

the world.

-

{some text missing} ... the

heat of fires that burn in regular succession from one place to another.

All of these possibilities conform

to the visible evidence.

|

|

|

093 |

The paths of the sun and moon vary with the seasons because:

-

A different

slant may be forced upon the heavens at different seasons.

-

There may be a wind blowing

across their lines of motion.

-

A required fuel is constantly

being set on fire in new places as it burns out in a prior ones.

-

Their motions have been

predetermined since the creation of the world to follow some sort of spiral.

Again, all these scenarios do not

contradict what we see, so we should go along with any of them, disregarding the

unquestioning techniques of astronomers.

|

|

|

094 |

The alternating phases of the moon are due to:

-

The rotation of the moon

itself.

-

From changing configurations of the air.

-

From the interposition of a body.

-

Any other way that has an earthly analogy.

Yet again, we must not be so

enamored with a unique explanation that we reject others without reason, failing

to understand the limits of human observation in our impossible desire for

certainty.

|

|

|

095 |

With regard to moonlight, either:

After all, many things in our

experience are observed to have their own light from themselves, many from

outside sources.

|

|

|

|

There is nothing about celestial phenomena which prevents us

from accepting any theory as possible if we always keep the principle of

plurality in mind as we examine the explanations and causes that are consistent

with the evidence. We should resist the explanations that are inconsistent

with the evidence, and not give them credibility without basis. Nor should

we fall back, in any way or on any occasion, upon the method of unique

explanations.

|

|

|

096 |

The appearance of a face on the moon may be the result of:

Again, we do not abandon this method

while investigating celestial phenomena; for if anyone contradicts clearly

observed facts, he will never be able to have true peace of mind.

|

|

|

|

Eclipses of the sun and the moon occur because:

Sometimes we must consider

compatible causes together, realizing that it is not impossible

for two causes to be in effect simultaneously.

|

{14} |

|

097 |

The regularity of celestial motions must be accounted for

like events on earth: without introducing the need of the gods. The

divine must be kept free from duties and in perfect happiness, otherwise all our

explanations of celestial phenomena will be in vain –

just as it is for those who ignore the method of the possible and vainly

stick to the belief that each phenomenon can only happen in one way. By

rejecting other possible causes, they are driven to unreasonable explanations,

and are unable to take into account the observations which signify other things.

|

|

|

098 |

The changing lengths of day and night may be due to:

Such things are observed to happen

in our earthly experience, so we must speak in a manner consistent with them

when we speak of phenomena of the sky. But those who insist on a

single cause oppose the evidence of the senses and have strayed far from the way

in which one may learn.

Weather |

|

|

099 |

Signs that predict the weather may be due to:

-

Mere coincidence, as is the

case with signs from animals we see.

-

The result of actual alternations and changes in the air.

Both are in harmony with phenomena,

but we cannot tell under what conditions a sign is due to one cause or another.

|

|

|

|

Clouds come into being and take shape when:

It is not impossible that cloud formation is also

produced in several other ways.

|

|

|

100 |

Rain can be produced from clouds if:

A more severe rain occurs when there is an

accumulation of what is needed to cause such a downpour.

|

|

|

|

Thunder could be caused by:

The evidence of our senses requires

that thunder, just like other things, may be produced in many ways.

|

|

|

101

102 |

Lightning may also have several causes; it could happen when:

-

A mass of

atoms prone to cause fire escape, which happens when:

-

Clouds rub against each

other or collide.

-

Such atoms are expelled

from the clouds by internal winds.

-

Atoms are squeezed out of

the clouds by pressure caused by

-

Other clouds.

-

External winds.

-

The light of stars has been

gathered together by the motion of the clouds, which then falls through

them.

-

The light from images have

filled the clouds so full that they have been lit on fire, and thunder

results from the fire’s motion.

-

The wind catches on fire,

either by:

-

Clouds are burst open by the

winds, causing the expulsion of atoms that cause fire, which take the form

of lightning.

It is easy to see other ways in

which lightning may happen if we stick to the evidence of the senses and are

able to compare it with similar earthly phenomena.

|

|

|

103 |

Lightning precedes thunder in a cloud formation because:

-

The mass of

atoms that forms the lightning is driven out of the cloud at the same time

that the blast of wind enters it; the wind pent up in the cloud then makes

the noise of thunder.

-

Both lightning and thunder

burst out of the cloud at the same time, but the former makes a quicker

journey to us, while the latter moves more slowly

– just

as it happens when we see person at a distance striking blows.

|

|

|

104 |

Lighting-bolts may be created when:

-

After many

gatherings of wind are repeatedly collected, trapped, and violently ignited,

part of a cloud is torn off and cast down, due to the fact that the

compression of the clouds has made the neighboring parts more dense.

-

The expulsion of interior fire

(of the kind that may cause thunder) when intensified by the wind to the